What about genre? Let’s not get caught up in the clanging of metal or flitting of folk. There are as many genres and subgenres as to have lost count. There are song types that are labelled but the fad finishes so fast that it falls into disuse. But for all its susceptibility genre has a useful purpose in subconsciously delineating its defining features.

Country music is earthy and celebrates life on the land. It talks about the trails and tribulations of life, love, companionship, home. There is glitter and rhinestones, don’t get me wrong, but the lyrical content has a modesty of intent. Later artists started getting increasingly gimmicky to keep the appeal of plowing the same field, with one behatted guitar-slinger declare he was “Lookin’ for Tics”. No music should, however, be judged by its most facile aspects.

Every permutation of love and heartbreak is attended somewhere along the line. These are popular subjects in many genres. Country music adopts a more courtly approach; Merle Haggard “We don’t make a party out of lovin’/We like holdin’ hands and pitchin’ woo”. The menfolk are as likely to get a serve, perhaps even more so. From being admonished to ‘Not come home a’drinkin’ with lovin’ on your mind’ to being accused en masse “Two hoots and a holler/The men ain’t worth a damn/Two hoots and a holler/They’re the lowest thing around”

Even when a partner is found to be cheating, there’s a bitter remorse at it “happening” like in the beautiful Tennessee Waltz where ‘my friend stole my sweetheart away‘ or coming off the poorer from a table with “Three cigarettes in the ashtray” rather than an excuse to cuss. It’s ‘Your Cheatin’ Heart’ not ‘You’re a Cheatin’ Harlot’

If you’re a national treasure you can write songs about different towns and then tour them. You’re guaranteed of good crowd reaction for at least one song.

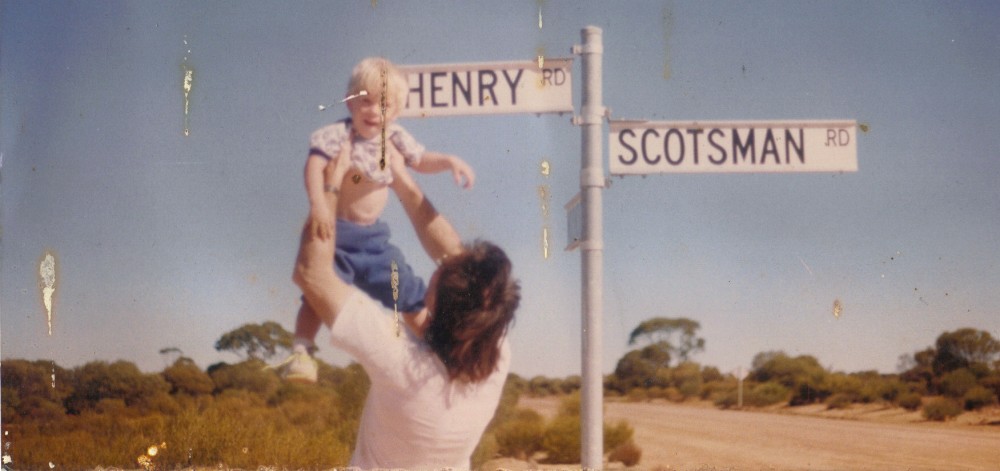

The first artist I would have seen live was Buddy Williams, an odd honour for him to possess given the array of singers and musicians I’ve watched since. But live entertainment was very much appreciated that far out in the country and there’s a real sense in which artists in this genre are writing to, for, and with the people living in remote rural communities.

One of his was ‘Way Out Where the White-face Cattle Roam’ but that was on a later recording so not sure why that one stuck. Early Slim Dusty takes its inspiration from the bush balladeers of the nineteenth century and also sings about pubs and mates. Country music isn’t given to too much trickery. Wordplay has to let the listener in on the joke. But it’s glorious when it does this well “If I said you had a beautiful body would you hold it against me” “All my exes live in Texas, that’s why I live in Tennessee”

Chad Morgan’s stock in trade is humorous songs about country weddings, country nutjobs, country hicks. Nothing’s sacred.

While country lyrics take a genteel approach to lovemaking – witness Charlie Rich suggesting what will go on once they get Behind Closed Doors or listen to Travis Tritt hearing his lover’s heart beating faster – death tends to be dealt with more bluntly, and there’s no sanction on singing of revenge and murder.

Occasionally country will stray into politics but usually only if the situation is extreme such as Hank Williams warning off Joe McCarthy in ‘No Joe’. Even then we wonder whether he’s not more of a folk performer when he addresses such topics. Topical events like The Pill or The Streak get a run and we can’t forget (much as we might like to) the conservative admonitions often as not culminating in boneheaded attempts at rousing patriotic sentiment for the agenda of the government of the day.

II

I don’t intend to look at features of all genres that closely as I feel that the songwriting process absorbs much of this understanding from a lifetime of listening (even half-listening) but I don’t think it hurts to see how genre operates.

Does this mean that you tailor your words to the expectations of what a country song is? Or what an alt country or Americana tune is? I remain consistent in my advice that you need to build songs up from the needs of the song and let things like genre take care of themselves. This wouldn’t work so well if you were thinking of writing ‘You Can’t Have a Hoedown Without Hoes’ but if you stay away from the cliche you’ll be better off anyway.

III

‘Towing Back’, ‘Tow It Back’ sound too topical to past muster, especially when the subject strays a little into the opposite camp. Even when my whimsy touched down on ‘Towin’ Back Your Heart’, I thought of the tangential ‘You Can’t Take It Back’ but, even as I was assembling the first lines in my head, I had an overwhelming sense that this would be more of a gritty R&B. Let’s see

You Can’t Take It Back

You give out hurt and hate galore

The darkest corners to explore

You surrender planned splendour

Release a real ease of movement

The impact that sells improvement

But you can’t take it back

You give away the things you say

Watching it all come into play

You abandon the cause you stand on

Throw the game of second chance

While circling round a circumstance

No you can’t take it back

IV

I don’t think it fits either genre. It’s more my choppy style laden with different readings. You may encounter other stylistic tics that take you away from the country. This is only a problem if you’ve taken on the wording for a hoedown or been given the task of pitching some lyrics for a country & western song. As for alt-country, for the purposes of this exercise, I want to stick to a more traditional form even among more contemporary songwriters.

I’d thus suggest an approach more along the lines of:

You Can’t Take It Back

You gave me years of turns at tears

You gave me an escape

You surrendered your pretended

coy ploys and attack

You can’t take it back

You lent me rent me circumvent me

You turned me inside and out

You pawed me and ignored me

at the first prospect you lack

You can’t take it back

What you offered and you proffered

Off colour and profane

You slid across the chrome embossed

dream all dressed in black

You can’t take it back